Amanda Green travelled to Kathmandu, Nepal, for her overseas placement. She now works as a qualified midwife in the West Country and says that her trip with Work the World was instrumental in helping her get to where she is today.

We caught up with Amanda to find out more.

So, what was it that made you want to study midwifery?

So, what was it that made you want to study midwifery?

I lost my husband when I was pretty young, and that changed my whole outlook on life.

At 42, I was bringing up two children on my own, having nursed my husband through a terminal illness. I got to a point where I thought, “What am I going to do with my life now?”

I waited until my son and daughter were a bit older and thoughtI never would, "If I didn’t do something now." So I took an access course and applied for a midwifery degree, and now here I am—a qualified midwife!

You studied at Plymouth — can you tell us a bit about your time there?

It was amazing. I have no point of comparison, but I loved my experience there. It was tough, though—midwifery is one of the most time-consuming degrees you can pursue.

Throughout the three-year degree, I had to complete 2,800 hours of clinical practice, in addition to the academic side of the course.

And how did Plymouth support you when it came to undertaking your trip with us?

I did some fundraising and applied for grants and bursaries to help pay for my trip. One of these grants was from a fund set up by the widow of a professor who worked at the university. One of the buildings in the university is named after him.

The grants are for students who want to get experience outside of the university structure to develop whatever they are studying, which can benefit others in the future.

They awarded me £900, which was amazing. My tutors and lecturers also fully supported my placement overseas.

I was scheduled to give a talk to the second-year Plymouth midwifery students on the ‘Developing midwifery practice’ part of the degree, sharing my experiences with the colleague I travelled with.

Now, regarding your clinical experience in the hospital in Nepal, can you tell us a bit about the difference in care between there and the UK?

Something that struck us was that there was no intervention in the low-risk birthing centre.

You’d never see anyone breaking a woman’s waters, for example.

In the trust I work in, if a baby’s head doesn’t come down after a prolonged period of pushing and the woman isn’t able to empty her bladder to make room for the baby, we may use an ‘in/out’ catheter to quickly assist in emptying the bladder, which can also prevent bladder damage.

We witnessed one woman pushing for an incredibly long time without any intervention like this. Local staff popped an ice pack where her bladder would be, which they said was supposed to help. Even if they had chosen to intervene in the way we do in the UK, they wouldn’t have had the sterile catheters to do it — resources were so low.

Another case that has stayed with me happened on my first day in the hospital. There was a woman who was in preterm labour at around 32 weeks gestation.

In the UK, that baby would have every bit of available support. The neonatal team would be there, the mother would have been given steroids to help with the baby’s lung development, magnesium sulphate to provide neuroprotection, and the resuscitaire would be ready with oxygen and suction.

In Kathmandu, they didn’t have access to those things. In this case, the mother had to go it alone — she gave birth without the support of her partner. The baby wasn’t breathing, and they didn’t have any oxygen for it because the hospital’s one working resuscitaire was in use.

The staff didn’t t perform any type of resuscitation, such as inflation breaths, the way we’re taught to in the UK. In the end, they had to take the other baby off the resuscitaire and swap the new baby in. But, there was a 6-minute delay in getting the baby any treatment or oxygen. It was hard to watch, but we were there to observe and not intervene. I want to add that we always obtained consent to be present in any given situation.

Another big difference was that in the high-risk birthing centre, women had to labour on their own. They weren’t allowed anyone in with them for support, and there was no pain relief at all. Labouring women’s mothers were allowed to run in with a bowl of soup or drink — they were given a liquid diet during labour — but that was it.

They were expected to walk into a different room to birth the baby once fully dilated. Very little monitoring took place due to a lack of equipment. My colleague and I raised funds to donate two Dopplers.

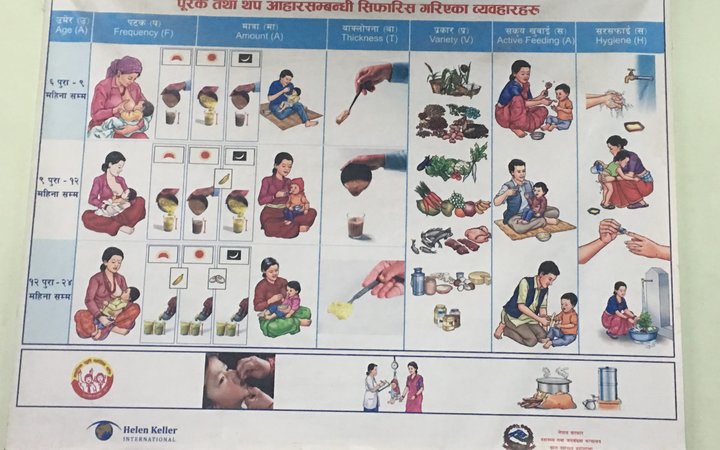

Conversely, in the low-risk birthing centre, they were starting to allow partners to come in with women once in labour and sometimes mothers as well. They’d begun to understand the benefit a support person can give and how it can help the women in labour cope. They were very interested to learn how we do things in the UK.

While I was there, we taught some of the dads how a lower back massage can help with the pain. You could sense that they were terrified to be near the women because it’s not a cultural norm. We had to reassure them a little, but you could sense the women were happy not to be alone.

One thing that surprised me was that all the notes were written in English, all the medical terms were the same, and women were offered scans as they are in the UK.

Do you feel like experiences like that have changed your approach to midwifery now that you’re back at home and qualified?

It certainly made me realise the importance of things like the yearly skill updates NHS midwives get. We undertake e-learning, training days and "drills and skills" sessions in obstetric emergencies. With neonatal life support, for example, you perform, with examiners, a practical demonstration of neonatal resuscitation. You have to pass a written exam afterwards, and you then have to update that every three years. These skills save lives, which I appreciate so much more now because you could find yourself in a situation like the one I described above. They didn’t appear to have had much in the way of that sort of training in Nepal, from what we saw, And they often wouldn’t have the drugs or equipment they needed even if they did.

I feel very grateful for our available resources, as I have witnessed global health inequalities first-hand. I also have a much better understanding of cultural diversity, which, when caring for women of many different ethnic backgrounds, I believe makes me a better midwife.

Do you have any words of encouragement or wisdom for students who might be hesitant about undertaking a placement like this in a country they’ve never been to?

I would say go for it. I travelled with somebody, but even if you're going alone, you get to know the other people in the Work the World house, and you’ll make friends quickly enough.

When you arrive, the Work the World staff will meet you at the airport and take you to the house. We all felt completely safe while there and were well looked after the whole time.

When it comes to the placement, you know where you will be before you even travel.

Take full advantage of it — it’s a once-in-a-lifetime experience.

Discover more about our Electives in Asia; you'll find a range of unique destinations that offer eye-opening clinical experiences and adventures.

Next Steps

WHERE TO?

Want to go on a life-changing trip like Amanda's?

Choose your destination below to get started.

Want to go on a life-changing trip like Amanda's?

Choose your destination below to get started.